In the soft quiet of an idle afternoon, thoughts start to stretch. The mind, unsupervised and restless, pokes at its edges. A moment that begins with nothing in particular can veer, almost imperceptibly, toward something reckless. That’s often how boredom and stress, the opposites of mindfulness and wellness, open a path to curious choices that feel harmless at first but aren’t always easy to walk back.

Reducing Risk Through Awareness and Redirection

Prevention does not mean suppressing curiosity. It means understanding what drives it and giving it structure. When young people understand how boredom and stress affect their thoughts, they gain the ability to pause and assess. They can learn to ask: Why am I interested in this right now?

Curiosity needs to be honored. But in youth development programs, experts stress the importance of “safe containers” — activities or spaces that invite exploration without danger. Structured creative time, guided online research, real-world problem-solving tasks, and supervised social activities can help. They satisfy the same need but with support.

Parents and educators also play a role. Conversations about curiosity should not begin only after something goes wrong. They should happen when things seem calm. When a teen says they’re bored, or looks overwhelmed, it’s a signal—not a nuisance. It’s a doorway to connection.

And when substance use or peer pressure is involved, the dangers of experimenting with drugs become more evident. Even one-time decisions driven by curiosity can establish a pattern. Curiosity is powerful. It shapes behavior more than fear does.

The Pull of the Unknown in Quiet Moments

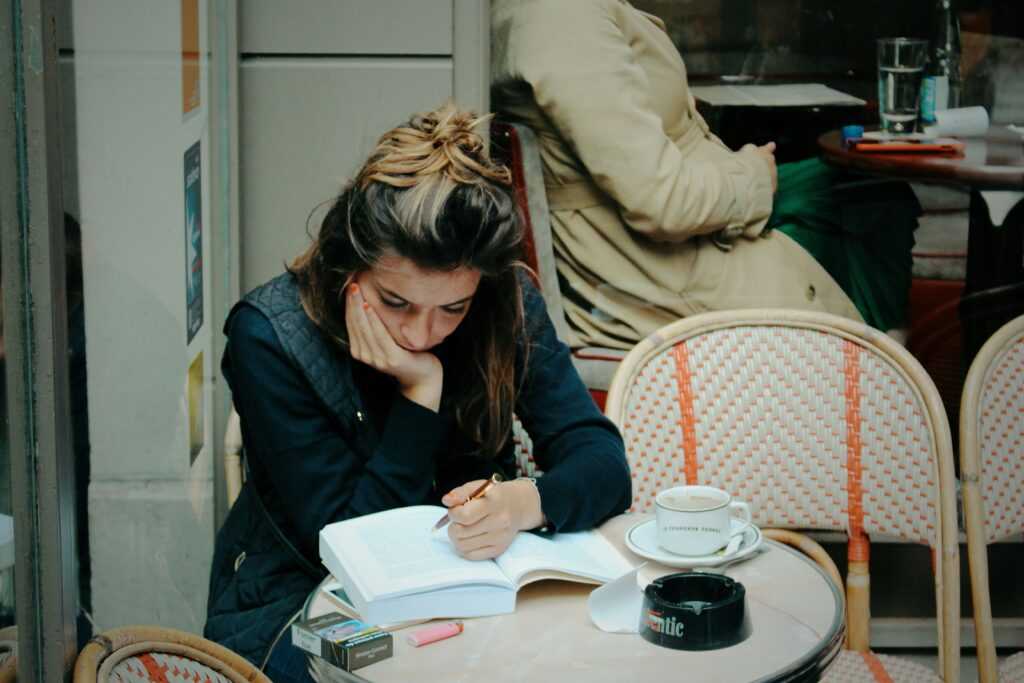

There’s a kind of itch that settles in when nothing demands attention. Boredom doesn’t just mean stillness — it generates tension. The hours feel longer, the senses go looking. That restlessness becomes a kind of invitation. When usual distractions lose their pull, novelty becomes more appealing. And not all novelty is safe.

Studies show that boredom is linked with impulsivity. People who experienced frequent, sustained boredom were far more likely to seek new experiences without thinking through the risks.

Boredom has a way of making ordinary rules feel less relevant. It does not push directly. It waits. Then, in the quiet, it lets curiosity stir. What starts as a harmless click or question can quickly escalate, especially when there’s no one watching closely. Curiosity itself isn’t dangerous, but boredom can strip away the filters that normally shape it.

When Stress Fuels Escape and Impulses

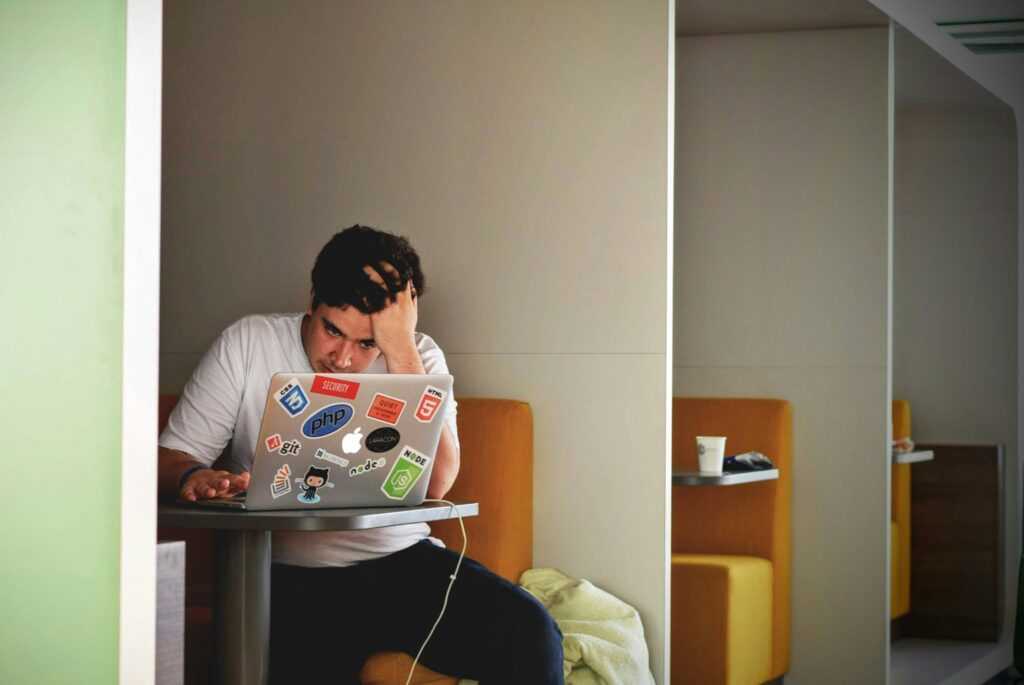

Stress moves differently, especially with anxiety disorders. It doesn’t stretch time. It tightens it. And in that compression, it changes how people explore. Curiosity under stress isn’t passive. It reaches. It needs something to interrupt the pressure.

In stressed states, the brain shifts. It wants relief more than insight. That can make risk feel like a shortcut. The risk might be small — staying up too late, skipping meals — but it can also escalate. When curiosity serves as a distraction, the boundaries of that exploration become harder to hold. What matters is not what’s being discovered, but what’s being avoided.

Boredom and stress together create a fragile structure. Curiosity inside that frame tends to grow fast and move without direction.

Combined Forces: Curiosity With No Brake

The intersection of boredom and stress is where risk rises fastest. While boredom extends time and draws attention outward, stress fuels urgency and turns curiosity into a coping tool. Together, they blur the boundary between what is safe and what is simply available.

This is not rare. Mental health professionals say they see more cases where curiosity linked to these emotional states leads to self-harm behaviors, exposure to risky content, or substance experimentation — and with more than nutritional supplements.

The decision isn’t planned. It’s drifting. The opportunity appears, and the moment feels right to try it.

Risky curiosity doesn’t always stem from thrill-seeking. Sometimes, it grows out of a quiet urge to feel different, even for a moment.

How Risk Hides in Curiosity

Risky curiosity is hard to spot. It doesn’t always come with warning signs like defiance or withdrawal. Instead, it often surfaces as increased screen time, a change in language, or subtle detachment from routine interests. Adults may overlook these changes as typical mood swings or teen distraction.

But inside, the driver is clear: something feels off. There’s no stimulation, or there’s too much pressure. The middle ground — the place where reflection, growth, and healthy curiosity live — vanishes. What remains is the urge to “try something new,” without the tools to assess what that means.

Digital spaces amplify this. Online, curiosity finds quick answers but also risky pathways. Algorithms do not judge. They serve what they see clicked. So one curious question can lead to a set of progressively riskier suggestions. Without intervention, that digital curiosity can spiral.

One article, one video, one conversation can cross the line. In moments of boredom and stress, that line can vanish.

Supporting Healthy Curiosity

Teaching how curiosity works—what triggers it, what it wants, how it grows — can impact outcomes. Programs that include emotional literacy, stress management, and digital media education show promise. They don’t treat curiosity as a problem. They treat it as a signal.

The goal is not to reduce curiosity. It is to equip young people to guide it. That starts with noticing the moment. “I’m bored.” “I’m stressed.” Those thoughts are cues. With reflection, they don’t have to lead to danger. They can point toward questions that heal rather than harm. We often tell kids to be careful. But we rarely tell them how to be curious with care.

Curiosity does not come with instructions. But it can come with support. And when boredom and stress are present, that support is most needed.